Corfu Walks With Hilary

By Theresa Nicholas

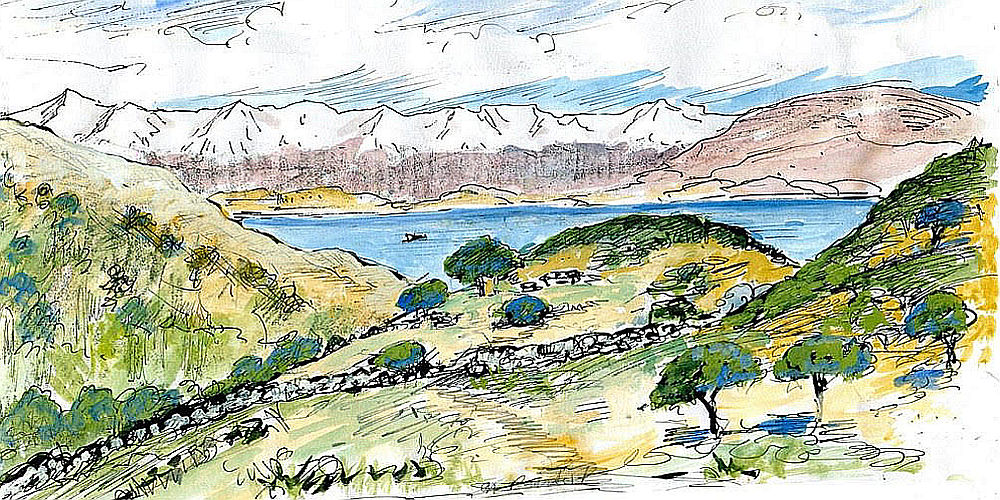

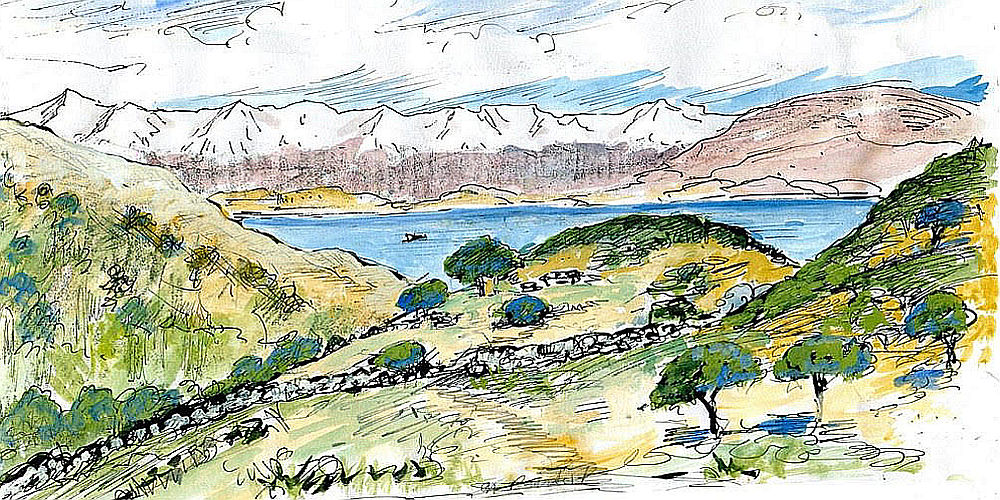

Above is Theresa’s sketch of the view from Mengoulas

March 9, 1995 The Pilgrim’s Way

My first walk with Hilary, after my previous walking companion Ann Nash had to give up. What a walk! The day began with rain. Hilary rang me about it. We decided to wait till 10.30. She rang again. At 10.30 the sun was brilliant. When she picked me up at 10.45, it was grey again and threatening more rain. The mountain was obscured by mist. It was our intention to do the Spartillas way up to the little chapel and over to Strinilas. It is my job to show her the route. I had done it once before with Ann two years ago. By the time we got to Spartillas, the weather looked settled to rain. Heavy mist above on the mountain. But off we went.

It is a spectacular old path up a ravine. Hardly ever used now. We had to fight our way through prickly bushes to keep to the path. Lost it a couple of times. By now it was raining. The mist came flying up the gulley like smoke from a forest fire. We were too near the top to go back, and going back would have been hell.

‘I hope the little chapel is open. It was last time.’ I said.

We surfaced onto the rim of the plateau. Having seen tin foil packets of crisps on the way up, I hoped we would not find a colony of Albanians living in this pocket of the mountain. [After the Communist regime fell, many illegal Albanian migrants headed for Corfu, smuggled in across the channel to north Corfu.]

The little chapel was open. It was raining hard now with thunder and lightning. It was 1 pm. So we had our sandwiches inside the church. Hilary’s clothing was not rainproof, but she is staunch and was still keen. The frescoes in that little church are very fine, but rubbing away of course.

I was beginning to wonder how we where going to emerge from this walk - dead from being struck by lightning? Or alive and lost? The mist blotted out all the landmarks. I was the one who was supposed to know the way out of this predicament. We left the chapel in a hailstorm. I was wanting to go left around the existing terraces - but the visibility was only a couple of yards. There was a path from the church which I felt was going too much to the right. Hilary suggested we stick to it, which was the right decision. Though, to me, it wasn’t going where I wanted, but it was a marked with red painted crosses. So we stuck to it. The red crosses were very reassuring, and took us through an ilex copse nearly overgrown. We went astray once or twice. The thick cover of the bushes sheltered us from some of the storm and the lightning.

I knew we must get to the new bulldozed track which, with relief, we did. It was not the way I would have gone had I been able to locate it properly. But, thank God for those red crosses. In fact they mark the old pilgrim path to the monastery at the very peak of the mountain, where the television aerial now is. I remember one night in the ‘60‘s, driving back from Dassia, we saw many village people on the roads with their donkeys piled with blankets and food stuff. They were walking up to the Monastery during the cool of the night to celebrate its annual festival.

Finally the bulldozed track cut right across the Pilgrim path, and we scrambled to it over the scree. Now I knew exactly where we were. Squelching by now, boots full of water, we could have been on Bodmin Moor or in a Scottish bog. I found the way down by the wells to the valley below Strinilas and the monastery.

By now we were simply walking through the water - after so much rain the place was awash. We gained the asphalt road. We had at least two kilometres to slog back to Spartillas. ’Oh, let’s hitch a lift,’ said Hilary. There’s not much traffic along this road in winter, but luckily a Rothman’s van came by as if ordered like a taxi. Hilary stuck her thumb out and the van stopped. The nice driver let us pack our wet bodies in beside him, and dropped us off right by Hilary’s car.

Hilary managed to change her sopping wet clothes for the dry things she had in the car. Her legs quite pink. It was like struggling with swimming things. She was still full of enthusiasm for the walk. No moans. She had just the sort of grit that keeps me steady. Her idea to keep to whatever path there was, was the right decision. God knows where we might be now if I had tried to rely on my sense of direction in that thick mist. Bless those red crosses. It was a great adventure.

[Editor: It was a no-brainer to chose this way between Spartillas and Pantokrator for the crossing of the Pantokrator Massif, following the red crosses, now weathered away and replaced with our own signs and others. For centuries, if not longer, this was the pre-road route taken by pilgrims heading on foot for the Pantokrator Monastery for its two-day August 6th festival. The monastery is said to occupy the site of an ancient temple dedicated to Zeus, meaning that the path may date back millennia. Subsequent to its re-establishment as a modern walking way, which has kept it clear, various hiking and trail-running operations took advantage of its existence for their own route planning. If during research for the Trail Theresa and I had not found the overgrown and almost-vanished path, it would have been lost to all. This was the first of many recce walks with Theresa, of which some are remembered below.]

16 March, 1995 Spartillas and Sokraki

I took Hilary from Sokraki across the plateau through the vineyards, up through the cypress wood, on to Spartillas. Hilary is anti-asphalt. She will not walk on roads, only by paths and ways, though this road is pretty and truly rural with 25 bends to the summit.

To avoid the short piece of road we went down the old way from Sokraki into the valley of the Melisoudi river - a long circuitous descent. It’s a splendid old cobbled way, then we had use the ‘rejected‘ asphalt road - I was able to tempt her with a church for our picnic place. By now I needed sustaining, though my legs were going well.

The church above the despised asphalt road turned out to be a perfect place, with the retaining walls around the church carrying a sea of anemones, all different shades from pale to deepest mauve, and ‘wild widows’ i.e widow Irises. It was difficult to avoid sitting on them. Thank God, Hilary has taken up the picnic practice, and ended up eating more than I did. This so happens with people who say they never eat lunch.

We set off again toward Zigos. We had seen anemone blandas galore in the terraces after the cypress wood, and masses of ’widow irises’; it’s all happening and so much more to come.

I led her along the broad track - she doesn’t mind a broad track so long as it is not asphalt. Though the road is just as rural and pretty. That’s Hilary - the purist.

A woman picking olives warned us that this track ’goes nowhere’. I said I knew that. Another old woman with a donkey screeched us, ’ ’Po pas?’ ‘Where you going?’ ’Spartillas,’ I said. ‘SPARTILLAS! It doesn’t go to Spartillas! Spartillas from here? Never!’ I said I had been many times this way, but nothing could convince her you could get to Spartillas from there.

She was at least 50 and had lived in the valley all her life. Such are the confines of the mind. The mind makes a prison.

By now Hilary began to have doubts that I could do what I said I could. The broad track ends at a cypress coppice. A modest path leads on to the greatest delight of all - the Rock Pool. She was really taken aback by that. I led the way across it. I had expected it to be in spate and that we might have to paddle, but we got across by the stones without wetting our boots. It’s a delightfully varied walk. Now we were walking along abandoned terraces - abandoned for a perhaps century to cypress - so many big cypresses and the orchids that grow in profusion there. The pyramids, the italicas, and we came upon many Giant Orchids.

The path becomes a water course - so on up onto the road within a short distance now of Hilary’s car. Her enthusiasm is delightful. Though by helping her to make her book of Walks on Corfu, I don’t know if I am doing the island a service or a disservice. But in reality few tourist get here - and the season for walking is so limited. Too soon it is too hot to tackle a walk like this.

[Editor: I remember little of this walk, only the churchyard covered with anemones, and the obstructive behaviour of the local women, plus the orchid terraces where I was later to take botany groups, before they ruined it. The way from Sokraki into the Melisoudi river valley was another old cobbled footpath which became a section of the Trail, part of the route between Valanio and Sokraki. One route we originally considered for the Trail was the path from the ‘Rock Pool’ to Spartillas, only some vandal bulldozed it, and destroyed the magnificent cypresses, and the orchid terraces too. The way out of Sokraki that we finally picked was a beautiful forest path towards Spartillas, almost blocked by disuse. Theresa showed me this path, and the Corfu Trail recovered it for walkers.]

20 January 1996 The Albanian Immigrants’ Secret Landing Spot

Hilary picked me up at 10.30 and we drove over the centre north via Spartillas and Lafki, and down to Acharavi to the St Spiridon peninsula, which is almost an island, like a cork stuck in the neck of a small lake. We walked round this peninsula, with bone-grey rocks, the bluest sea between us and Albania with its stickle backed mountains. No snow, except on the furthest range.

This peninsula is different from anything else on Corfu. The northernmost tip of the island. We walked round its rocky shore line, then up and over the top into a wild olive wood entirely left to rampage unchecked. It was like walking through a 19th century painting - the way those artists painted trees, all silver leaves. As we emerged from this, there was a ruin on the left we had seen from the shore. From there it had looked insignificant, but from behind it was more extensive. Hilary knew about it. ‘It’s the old ruined nunnery of Agia Ekaterina.’ We went to look at it.

A wire gate closed it off, but it was open with a padlock hanging on it. Obviously it was being use it as a sheep pen. A Datsun van stood in the compound. We pushed inside, no dog barked. So we wandered across the yard to look at the ruins of the cloisters and the church. The church had a spectacular door. I wanted to sketch it to add to my collection. Hilary handed me her pad and pen. I was drawing it when a man appeared and came over to us with a very aggressive manner, demanding what we were doing.

‘She’s sketching the door,’ said Hilary in Greek.

‘It is FORBIDDEN!’ he said.

‘Forbidden to sketch?’ said Hilary.

’Forbidden to draw or make photo. Get out of here!’ the man insisted.

Hilary stood her ground, ’We’ll go in our own time,’ she said.

‘I’ll call the Police!’ he shouted.

‘Call them,’ she said,’ I know all the Police! Anyway, this belongs to the Church and we are entitled to look at it.’

He insisted it was an archaeological site, and we were forbidden to enter.

’Nonsense!’ said Hilary, ’I know the Head of the Archaeological Sites!’

Then he insisted it was his property and that we were trespassing. He made movements as if to go to fetch the police.

Suddenly, a young Albanian wandered into the yard to see what the fuss was about. Then both Hilary and I realised the man must be harbouring illegal immigrants and was terrified of us. This remote place must be a staging post for Albanians dropped off on the north coast of the island. It is just the sort of place they would use. No wonder he was so aggressive. The man became almost violent. ’Get Out Of Here!’ Shouting and waving his arms as if he would strike Hilary. He was like a bantam cock. Hilary was equally like a bantam cock, standing up to him. ’Go on sketching,’ she said to me. ’I’m not going to be bullied!’ She’s got guts!

It was an unpleasant experience. Often the peasants can be aggressive but when you speak to them in Greek, they become friendly and helpful - not this man. He was frightened by his own fears into anger - the anger of fear.

We sauntered slowly toward the gate and out. Unluckily, I had left my good walking stick behind, put down when I started sketching. It is a good expensive stick, but it wasn’t worth going back to get it. The man was so enraged he might be dangerous. So we let it go. Undoubtedly, he had much to hide. Albania is only a short distance away. The Greeks run an illegal ferry service with fast motor boats bringing Albanians across. This would be the perfect place to drop them off. This man would be taking money from them. The Albanians would then walk over the mountain toward the town. (Ann and I had once come across a group of six men when walking the mountain.)

It was quite an adventure. We walked back to the car through a pine forest and drove back via Kassiopi, stopping off at Kontokali at the Locanda English Pub. This was also an experience. It was full of people, all British! Young to middle-aged. All existing here in one way or another. What a contrast with the Albanian immigrants. Ironic.

It was a lovely day apart from the man and losing my valuable stick.

[Editor: This headland is the last section of the Trail, which runs along the low coastal cliffs. No Albanian migrants in hiding today! The church is falling down.]

15 February 1996 Benitses Waterworks

Hilary is making her ‘Drive and Walk’ brochure. She picked me up at the causeway 9.30. We went up to Gastouri and walked through the alleys of the village to the Empress’s Spring at Platonas, then by the old cobbled path through the olive terraces by a track up onto the little church on the peak. I nearly had a bad slip on the wet stone staircase, luckily saved by the hand rail. It has rained so much this winter the ground can take no more, and still it rains.

Next we drove down to Benitses. And started walking up to the old Water Works built by Adams to supply the Town of Corfu. I had never done this. The first part of the walk is through Benitses village, out the back of it by rather unattractive asphalt roads. Knowing how many times Hilary has rejected an asphalt road, I said, ’Do we have to do this walk?’ ’Yes - you’ll see…’

Suddenly, once through the little clutch of houses, it improved a lot, following the pipeline on a mini viaduct, then by a narrow path, getting very overgrown, and then by slippery steps upward to the magnificent waterfall, which we approached by a tunnel under the viaduct till we stood on the edge of a cataract going down a narrow ravine. It was spectacular. With all the rain it was full of water. Hilary said she hadn’t see it like this. I was being favoured.

We climbed up further to another level at the top of the cataract. And then higher still to the little Church which guards the waters. It was a revelation to me. All set in dense forest terraces. Quite different to other parts of Corfu. It could have been Tibet, the little plots of land with irrigation channels. The bits of rag on sticks to scare the birds were like prayer flags. We came down by an alternate path as the way up, though romantic, was falling away and getting grown over, so more difficult to descend than to go up it. Pity. It was a such a delightful walk once away from the asphalt and development.

[Editor: Benitses provides overnight accommodation for Trail walkers who cannot find a place in the mountain village of Stavros, where beds are limited. This is the best way down to the sea, even though it is off the main course of the Trail. The Water Works path is reasonably clear.]

10 March 1996 Episkepsis, Forni and Lafki

I was to show Hilary the connection between Episkepsis, Forni to Lafki. The way up past Forni with all the tree spurge in bloom. Masses of it. We came back the same way, and it was even better looking down on the large Mediterranean spurge frothing yellow, foaming over the limestone rocks and among the dry-stone walls. Forni is one of the unspoiled pockets of the island. A small cluster of old houses, still inhabited, tucked under a limestone escarpment. The path winds up by dry stone walls, passing above the houses, and then down the other side and mounts up toward Trimodi. On the way down we branched off to some old dwellings - a perfect rural setting surrounded by olives and almond trees.

We found an abandoned cottage with the old style kitchen with the three-tiered canopy over the fireplace. Niche-like cupboards; the bake oven just deep hole in the wall for baking the bread. The old chair and table, the tiny homemade settle like a child’s chair. Perfect.

We ate our picnic on the veranda looking over to Trimodi across a fertile ravine cultivated with vines and olives, nut trees. The shrubs coming into new green and some blossom still on the almonds. The birdsong babbling like a little river - a mid-day ‘dawn chorus’. Birds are often more vocal on grey wet days, I’ve noticed. It was memorable for the large Mediterranean Spurge; I’ve never seen such abundance.

[Editor: The connections we explored on this day were judged to be possible routes for the Trail on its descent from Pantokrator. In the end, the Corfu Trail friend Fried Aumann rediscovered the old path down from Old Perithia and the Parigori Gorge towards the coast, and that path became the final choice for the course of the Trail’s last section.]

15 January 1997 Ano Pavliana & the ‘Capetanos’

Hilary said she could walk Wednesday. Would the weather be clear or revert to grey cloud and rain? At 6 am the stars were sharp and bright. It was going to be good if cold and crisp with frost. 8 in the morning. Telephone rang. Hilary: ‘Are we on?’ Yes! I had to meet her at the causeway 9 so I had to scramble, make breakfast, a sandwich, some coffee and walk the 20 minutes to the other side of the causeway.

On the causeway, I had time to watch a Great White Heron fishing, the neck like a hook holding the blade-like beak poised to strike. I saw a Kingfisher fishing too. He was sitting on a post in the water. Suddenly he dived down and up again in an instant. What an aviation feat, regaining his perch while gulping his prey. A more merciful death for a fish than being caught by man. It’s a clean efficient kill that comes from nowhere and does not have to be feared.

Hilary picked me up, we drove south to Vouniatades. Leaving the car at the edge of the village we walked back through the village. Hilary asked two old men, loafing about, for the old path to the village of Ano Pavliana. We got the replies we expected: ‘Oh, you can’t go by the old path. It’s closed. It’s difficult,’ etc. And they point to the asphalt road as the only connection. The old man was adamant. Hilary was adamant, too - we would see if we could find the Old Way. This happens so often: the natives telling you the old paths go nowhere or don’t exist. We know now to deliberately ignore it. All we need is the starting point, so off we went by the very way they had indicated as impossible.

We found an excellent track taking us in the right direction and then when the way did peter out, a jeep came bouncing toward us through the olives on no visible track. Hilary stopped it to ask where it had come from. The driver of the jeep was a lively middle-aged Greek wearing a baseball cap. His companion, a young woman, his daughter probably. He was instantly ready to enter into what we wanted to do. They both looked at Hilary’s map, an old ordinance map of 50 years ago. He had come from Kato Pavliana, an adjacent village. They neither of them believed it was possible to get up to Ano Pavliana, but he leapt out of the jeep and pointed out certain features and what to make for. He told us he had been a captain in ships so we called him ‘Capetanos’ (the Captain).

The two villages are on a shelf above us with the mountain behind them. We wanted to get up and over and eventually down the other side to join with Paramonas. It’s like asking for the moon to them, but he cheered us on and drove off.

We walked in the direction they had come from by no visible track and came to a sticky muddy river of clay. We couldn’t see how the jeep had come this way, and began to imagine it had dropped from heaven. We crossed the clay river, which looked as if a herd of zebra passed through it, and picked up a cobbled way, followed that until we met another peasant and asked for the old pathway - again the performance of heading the local mind away from the concept of a car and four wheels as the only method of getting anywhere now. It’s not as if Hilary isn’t fluent in Greek (though her accent is English). It is the mind of the recipient which has to be re-educated to accept the obsolete idea of going these distances by foot. There is the initial look of bovine astonishment, and then the categorical denial of the existence of the tracks which once carried them from village to village before the creation of the roads and cars. They make movements as for steering wheels. We slap our lower legs indicating that we go ‘by the feet’ and don’t want an asphalt road! And still they direct us to the asphalt! It is the new mentality.

Then comes the sudden collapse. ‘Oh well, if you want the old path it’s over there. BUT IT DOESN’T GO ANYWHERE!’ By which we understand it is the one we want and take to it with joy. ’It’s broken now - you won’t find your way,’ he calls after us. Never mind! we say, and taking it we achieved our objective: the village of Ano Pavliana.

The same performance with identical responses we get in Ano Pavliana when asking for the footpath out of the village up onto the mountain. No, we don’t want the asphalt road. Again the two old gaffers try to put us off, before admitting that the footpath does go up there, and watch us go with heavy scepticism.

We found an excellent quick way up to the bulldozed track on the mountain. I’ve been up here twice before with Ann. It’s spectacular for the views across the island to the mainland mountains and the western coast. I had been skeptical at getting up here so easily, but overjoyed to be on these heights again where Hilary had never been. I was able to point out the track going down the other side to Pentati.

We walked the entire track to where it ends, and had our picnic in the same spot where I had been with Ann, looking over to the snow clad peaks of Albania; the sun clear and hot, but crisp and clean too. It couldn’t be a more perfect day. We had to return to Ano Pavliana by the same track, but going down the steep rugged path was no real hardship.

Once back in the village, we went toward Kato Pavliana and found a beautiful walkway through the steeply descending olives groves - a dark gesticulating ballet, all tree trunks peat-black from the recent rain. We encountered medieval scenes with peasants: men and woman collecting the olives. The women in this area are cheerful and medieval in appearance still, scarves locked round their heads, giving shade over the eyes; full skirts and sturdy legs terminating in feet clad in slippers - not boots such as we wear to cover the same ground. They are with their pretty chocolate-coloured donkeys, with straw bales on them. I haven’t seen so many beautiful donkeys as we saw today, with grey muzzles edged with dark velvet around the nostrils and white circles round the basilisk dark eyes.

These villages are largely unaffected by the tourism that passes through them on the way to the western beaches. The people responded to our greeting with a cheerful respect both for themselves and us, which is very pleasant. Often they almost burst like pods with curiosity as to what manner of people we are - at this time of year too - outside the season. Hilary smugly answers: ‘Having been on the island so long, we’re more Corfiot than the Corfiots!’

Our walkway brought us to the dreaded asphalt road. There seemed nobody around to ask until Hilary pitched her question at a group down in the olive grove that we had already passed. The men came out like voles from every crevice offering instructions. Hilary was adamant that we didn’t want the asphalt road, but the ‘monopati’ (footpath), and the ‘Paleo Dromo’ (old road). So they directed us toward the church where we found a way down.

Suddenly, a white jeep came up the track, the driver taking both hands off the wheel with gesticulations of recognition! It was the Capetanos again, and he stopped to greet us. We told him with pride where we had been. He directed us again back to the place where we had first met him. We found the way down the wide track. A woman in a patch alongside it swore it ‘went nowhere’, shaking her finger adamantly. Hilary said, ‘Yes it does! It becomes a monopati. The woman was crushed. They don’t move beyond their own patch: Beyond that ‘be devils’. Or ‘there be Dragons‘.

It’s fun going boldly were they never go. I was saying to Hilary ‘there must be a more direct way down from the village than this one.’ And, sure enough a cobbled way appeared on the right. I waited while Hilary ran up it right back into the village and returned triumphant. The whole purpose of this day was to find the viable track for Hilary’s tourist walks. So she was very happy.

We went on and found the new cement bridge across the small river at the point just after we had met the Capetanos the first time. We squiggled along awful messy way with clay sticking to our boots and regained the olive grove where we had met the ‘Capetanos’ in his jeep. So jubilantly we returned through the peaty black olive groves bathed in pools of bright green light, all flickering in sun and shadow like an early movie. And regained the centre of Vouniatades four hours after being told categorically we could not go that way. Alas, the same old codgers were no longer there so we couldn’t contradict them.

We regained the car, accosted yet again by an old woman: ‘Where have you come from? Where you going? Who or what are you? You must be Engliss. And where you go now?’ ‘To the car.’ ‘You have car?’ This information is received with evident relief. If you have a car you are serious people. To go ‘by the foot’ is to be downgraded, but the car has the reassurance that you are serious modern people.

Oh, what fun it was. We haven’t be able to do this for months because of the bad weather. And meeting the Capitanos was fun - our ‘Ariel’ or ‘Puck‘ as if sent to guide us. He had that kind of theatricality. A robust man about 56-60, which means he was born during the war and brought up in very tough times in a Greek village. Then went to sea and returns to his village to tend his own olives and make his own wine. The village has made progress but has not been hit by tourism. It has values the other places have lost.

In April 2008. I revisited this area with Laura. It was Easter Monday, the holiday. We were shocked by the change in these villages - all the character gone in modernisation. Aluminium doors and shutters. Pretentious pink villas built at the edges of the villages. It was really shocking. The Greeks have no respect for the old, see no beauty in it. Nothing worth keeping. New …New…. New… that is what they want, and they understand nothing else.

[Editor: More explorations along possible paths for the Trail, and indeed some became the routes it takes.]

1 February 1997 The Candlemas Walk

It is always more challenging to walk with Hilary because she is mapping out the walking routes so it is timed by the clock. We drove to Acharavi on the north coast to a part of the touristic grot deemed to be St. Simeon because there is a little church by the side of the main road with a huge olive tree beside it. A track beside it took us instantly into another world - a beautiful old way up into the foothills, like stepping through a time barrier, as if a door slammed shut behind us separating us from the suburban beach complexes, the grunge of touristic development.

We found ourselves walking up a broad grassy way among dry-stone walls with olive trees silvery grey-green, with flowers and grasses.

We came on a complex of old houses with more accommodation for animals than people. The living accommodation at the two ends of the building consist of one room upstairs where the families would have lived. All the centre blocks are for the animals. Behind the building were tangerine trees and vines, more olives trees - and a donkey.

he sun was shining strongly into our eyes, laying great blobs of light on the green grasses. Asphodel was already in flower standing shoulder-high. Clumps of early honeywort, plus marigolds, irises and deep magenta anemones. We went on round to the right, though the tracks went on in a straight course. Hilary knew where she wanted to go - swinging to the right as if back to the sea, then picked up a track going up to a ridge of oak trees. Lots of small oak trees, still all rusty and dead-looking against the other evergreens. It’s unusual to find so many oaks and proves the island was once covered in these trees. When the Venetians took over the island, they wanted the oaks for their ships, and cut them down, but gave the Corfiotes a ducat for every olive tree they planted. So the story goes…

The ridge had a good elevation with olive trees sinking steeply down to the bottom of a ravine where water flows. The opposite side rose up steeply too, also covered densely with olives. Looking upwards toward the foothills of the back of Pantokrator is impressive. It gives quite a different impression than anywhere else of the island. All you can see are the cones of the hills rising to the more barren parts of the mountain. It’s made up of more than one valley. The village of Episkepsis rides on the top of a hill of olive trees.

We descended the oak ridge to ford the stream - plenty of water in it. Then we joined the track through the valley which mounts steadily to the ridge where Episkepsis sits with the road going through it. To my amazement on getting to the edge of the village Hilary looks at her watch. ’You see, it’s only taken us 45 minutes.’ 45 minutes! No wonder I was feeling it! We were high enough to look back and see the oak ridge on which we had been miles away. And to where we would have to get back to, to find the car.

At one point we looked over and up toward Forni - that small cluster of houses riding under its limestone escarpment and resting like a boat on the sea of olives leaves. The olive trees lap the hills which rise up like petrified waves. Nothing modern intruded. We know the ways up to the highest hills now - and so, looking at them from here, we know what happens up there.

On we went. I was much in need of my sandwich. But with Hilary you don’t dilly-dally on the way. At 1 pm we did stop to eat our picnic. Then I was all right again - in fact performing very well.

We went down into the gully below Episkepsis village, then followed the lovely cobbled way up onto the next ridge. Hilary intended to swing toward Sfakera, but we came to a fork by a lovely house we recognised - a most romantic corner which I had always approached from below with Ann. No longer plotting her route, Hilary was willing to deviate, so we went ‘my way’, following a beautiful track which then gave out in a very steep deep dark olive grove with light at the bottom where we needed to get to. We were still pretty high up. The track into the valley we had ascended from was three hundred feet below us. We had already descended a hundred feet. This is where the ‘fairies’ lead you astray, and ‘to go back is more tedious than go o’er.’ So we opted for the steep slim footpath down through the olives, and steep it was. It’s always supposed to be easier going down. If it came to an end at the precipitous or overgrown area we would have been dished. And would have had to climb all the way back up. The thought of it was daunting. Even Hilary said she wouldn’t have wanted to do that. And I doubted if I could. It was psychologically a panicky moment for me. Have I bitten off more than I could chew? It is surprising how often you can be led astray on this island, and challenged physically.

Hilary was far ahead. I lumbered on down, shovelling on my bottom down the steep terraced walls. The olives were growing on narrow terraces so that we descended in zig-zags, a hundred feet in minutes. We did think we were dished at the bottom of one grove - then a way into a lower grove on the left bathed in green sunlight invited us and by great good fortune we discovered a hunter’s path leading out and down, till we could hear a tractor at the bottom. Even so it wasn’t simple. The path instead of joining the track swung away to the left at the bottom of a well-tended olive terraces towards some new houses. New houses never looked so good! I knew I was saved by those modern monstrosities.

We walked back along the old ‘main’ road through more dense olive groves, and some spots polluted by suburban symptoms – a fence, an ornamental well, and gateposts. Still I got back to the car in good style for me. There had been times when it can seem a very long way away! At least Hilary drives me all the way home, where I had a hot shower and hair wash and then crawled to the mini-market for milk and water and to boast of where I had been ‘me ta pothia!’ (on foot). Such fun to see their reaction:

‘Me ta pothia! Po, po, po!!!’ With your feet!!!

Another good day.

October 2000 Mengoulas

We came down through the old small clutch of houses called Mengoulas, on the side of the mountain. The houses beautifully stone-built with archways, places for shade, protection from sun and wind; deep sheltered verandas protecting from the heat, sun and wind. It is quite high on the mountain looking at Albania, from where the cold wind comes. I am so impressed by the way these old places are sited and thought out. They are not thrown into existence like the modern villas that take nothing into consideration but their own pretentiousness, built on the most exposed positions so that all the world can see them, and with the best views. Never mind protection against the sun and the wind, they have air conditioning and central heating. Badly conceived, badly built and vulgar. The only comfort one can take is that they will not stand the ’test of time’ as these good old stone building have done, with little maintenance.

[Editor: The Corfu Trail originally made a huge loop from the col under the Pantokrator summit, down to the North East Coast and back again, running through the gorgeous oak forest below Mengoulas and into the village itself. But because we discovered that many walkers were skipping across the neck of the loop, a matter of a couple of hundred metres, and cutting out the North East area altogether - and also because the construction of seafront villas has wiped out the original, stunning coastal footpath - we now leave it as an optional day walk that climbs to Mengoulas and then descends a different way to the coast.]