The Walls That Talk in Pelekas

Corfu Trail hikers may now enjoy a community arts and culture project called ‘The Walls That Talk’ which was launched at the start of July 2025 in Pelekas, central west Corfu. The village is one of very few inland settlements with a buzzing tourism trade, one well known for attracting artistic and alternative activities.

Over the course of the project, five acclaimed artists created large-scale murals inspired by local history, nature, and everyday life. Powerful examples of street art, the works were painted on derelict or ugly concrete walls, and they will leave a lasting artistic and inspirational legacy - one that beautifies the village and becomes a point of reference for both residents and visitors. All the works except one are located on the course of the Corfu Trail so that hikers may enjoy the artwork whilst proceeding through the village.

The project was funded to the tune of 25,000 euros by ANION - Ionian Islands Development Agency, under the interregional program ‘Island Circumnavigation - The Walls That Talk’, and was supported by the Environmental Association Green Pelekas and the Local Council of Pelekas.

To inaugurate the event, a major concert was held in the central square of Pelekas on 4 July 2025, featuring the internationally recognised musical duo Kantinelia, acclaimed through their impeccable live performances on both Greek and international stages. Their music offers a journey through the timeless sounds of Greece, reimagined through the melodies of acoustic guitars and the harmonious vocals of the two artists, whose signature style blends Greek traditional music with elements of blues and rock, to create a multicultural sonic fusion of East and West.

Most of the artworks are located along the course of the Trail as it runs along the main village street. The final one is installed on its offshoot to the popular viewpoint at Kaiser’s Throne, which Trailers staying in the village can head for as an early evening stroll.

As you reach the outskirts of the settlement on the track from Sinarades, hitting the main village road on the outside of a wide hairpin bend, a work by the artist Argiris Ser from Thessaloniki decorates a concrete cistern wall on the left. It comprises a rainbow coloured background half covered with undulating blue waves, appropriate to its aqueous mount. Its creator is an influential muralist specialising in street scenes. Now mainly based on the island, he recently exhibited at Corfu’s Municipal Gallery.

A short walk from the main village square, the road divides, with the Church of Saint Nicholas sitting in the fork. The road to the right heads for Kaiser’s Throne, ten minutes or so uphill, while the Trail takes the left-hand way. Just behind the church, the most extensive of the murals covers the wall of a derelict building. By Thessalonikan artist Ap Set, it comprises a giant hyperrealistic portrait of a woman wearing a traditional Corfiot head-dress, diminishing along the wall into a village scene with flowers.

On the neighbouring wall, on the other side of an alley, in early September 2025 Ap Set created a second artwork. The work features the elementals ‘Water and Air’ and is if anything more prodigious than his adjoining Corfiot Lady mural.

On the same wall as the Elementals, also to the right of the road, Simone Fontana from Thessaloniki has created an artwork featuring her signature motif of a ‘Manga Girl’ which in various iterations she has painted in locations such as Italy and the USA.

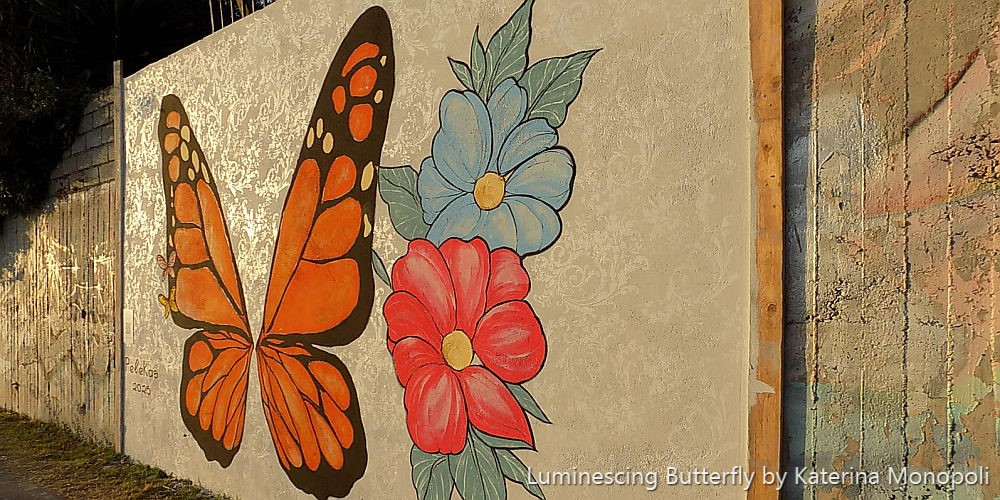

About a hundred metres on, shortly before the Trail leaves the village road on a footpath, a work by Corfiot artist Katerina Monopoli comprises a seemingly simple painting of butterfly wings and flowers. But the background, on initial viewing pure white, is overlayed with a complex pattern of scrollwork, which luminesces when the light falls on it at certain angles.

On the offshoot road that accesses the Kaiser’s Throne viewpoint, another artist from Thessaloniki called Rhino has painted a stylised Corfiot country scene featuring figures in traditional dress - women with clay pots, musicians in uniform - set against a background whose main landscape feature is a cross between Mouse Island and the summit of the Old Fortress.

Pelekas has a bit of a ‘street art’ tradition in decorating otherwise ugly structures. Some years ago, the local community ran for three seasons a popular ‘graffiti festival’ in which artists competed to create giant artworks on the concrete wall which borders the road leading up from the crossroads towards the village. Within the village, some minor murals have been painted on bare walls in the past, and more recently a set of wheelie bins on the approach to the centre has been embellished with painted motifs, which catch the eye as you approach the centre. But this latest project has taken street art to a new level.

A QR code is attached to each artwork so viewers can discover more about the artists and their work.

More info: wallstalks.com